Withdrawing money from a mobile money account in Uganda. Remittances are not only sent from the Global North but also increasingly within the Global South. Photo credit: Fiona Graham / WorldRemit

This article was written by Eric Reidy, Migration Editor-at-large of The New Humanitarian. The article can be accessed here.

Why do dominant media and political narratives about migration tend to focus on the relatively small number of refugees, asylum seekers, and migrants attempting to reach the Global North irregularly and overlook the important role of South-South migration in development, inequality, and humanitarian crises?

Because narratives about migration are dominated by media, politicians, and researchers in the Global North, Joseph Teye, director of the Centre for Migration Studies at the University of Ghana and co-director of MIDEQ, told The New Humanitarian. “Not everybody is moving to the Global North,” he noted. “The narratives have to change, and the narratives can only change when we decolonise the knowledge.”

Shifting the production of knowledge about migration toward the Global South is an effort that Teye and others have taken on at MIDEQ (Migration for Development and Equality), a hub of around 90 researchers. They study movement along six migration corridors between 12 countries in the Global South – one of the few research projects in the world dedicated to studying South-South migration.

The researchers are producing academic studies, policy briefs, and blogs about the dynamics and experiences of South-South migration to begin filling the knowledge gap. MIDEQ recently released an animated video aimed at bringing the idea of the need to shift migration narratives to a wider audience.

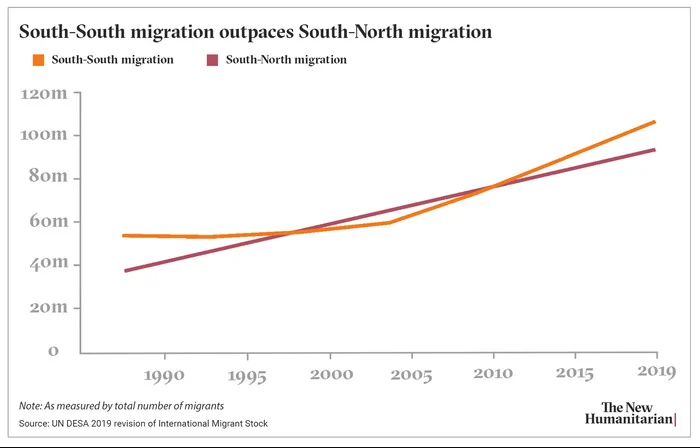

More people migrate within the Global South (around 37 percent of all migrants) than from the Global South to the Global North (around 35 percent). When it comes to refugees, 85 percent are hosted in the Global South.

Yet that’s not a reality that journalists and scholars in the Global North often focus on, Teye explained, noting that what they see is an influx of people coming to Europe, especially since 2015. So that’s the story they tell, which has become the dominant, North-led narrative.

“Decolonising the story means that the writing on migration, the research, the storytelling should be led by scholars from the Global South working with scholars in the Global North,” Teye urged.

MIDEQ is trying to foster that work, although its funding for this year was reduced by 70 percent in March after UK Research and Innovation, which backs the initiative, had its budget for international development research slashed by nearly 50 percent. The reduction is part of substantial budget cuts to UK international development spending that are having widespread ripple effects throughout the aid sector.

The New Humanitarian recently spoke to Teye about the relationship between South-South migration and humanitarian crises, the policy consequences of the disproportionate focus on South-North migration, and the urgency around decolonising and reframing the story of migration.

This interview has been condensed and edited for length and clarity.

The New Humanitarian: What do media narratives in the Global North often miss or get wrong about migration?

Joseph Teye: Usually, the narrative suggests an exodus from the Global South to the Global North. If you look at most of the countries in the Global South, most migrants move inter-regionally. They do not move to the Global North.

If you take Africa for instance, on average we have around 50 percent of migrants moving within Africa. But when you come to regions within Africa – West Africa, for example, which is portrayed as a source of irregular migration to Europe – then you have about 64 percent of migrants within West Africa moving to another destination in West Africa.

It was 80 percent in 1990. The decline is not because they are moving outside of Africa, but there are now new destinations outside West Africa, but still inside Africa, such as Gabon or Equatorial Guinea. The only region where you tend to have a higher proportion moving outside the region is Northern Africa, and they are not going to Europe. They are going to the Middle East.

If a majority of people move within their regions, then there is a need to look at South-South migration, which has been neglected in the media narratives and also political narratives. Everybody's focusing on South-North.

When we look at the impact of migration on development, if you think about remittances, the figures we’ve seen so far show that these are also increasingly sent within the region. Ghana, for example, receives a lot of remittances from Nigeria, Togo, and Burkina Faso. If you are ranking them, the US comes first, the UK comes second, then it goes to Nigeria, Togo, Burkina Faso.

But we hardly talk about this South-South migration and its impact on development and inequality.

The New Humanitarian: How does the disproportionate focus on South-North migration affect policy? I'm thinking specifically about West Africa, where there has been a lot of policy focus on restricting migration, and you're saying there's a lot of migration within the region. Does the focus on South-North migration have a negative impact?

Teye: First of all, there is a concentration on what is termed to be “irregular migration” outside the region. If you look at West Africa’s dealings with the European Union, within the last five years, most of the policies of the European Union are focusing on addressing the so-called “root causes of migration” for people migrating outside West Africa, such as poverty, climate change, and political issues.

We are not saying talking about those things is bad, but because of the focus on that, you realise the European Union’s externalisation policy in some West African countries, including Niger, is based on the assumption that everybody in West Africa is moving toward Europe. So the policies are trying to restrict mobility beyond Niger. But Niger has also signed a free-movement policy with other West African countries. So EU policies are restricting mobility, which has been a long-term part of livelihoods in West Africa and is something that West Africans don’t view as a problem.

Second, within West African countries, the focus on South-North migration means that when governments are designing policies to harness the benefits of migration – including remittances – they tend to focus only on diasporas that are in the Global North, such as the US, the UK, and Germany. They forget that there are also diasporas within their region that could be tapped for development. Unless we present data to governments to show that people within that region can also contribute to development, that is not thought about at all.

Lastly, when it comes to protection of migrants and dealing with inequality issues, again the focus is only on the South-North. Nobody is talking about migrants that are still within the region. So, there is a mismatch between the situation on the ground and the policies that are coming out.

The New Humanitarian: A recent MIDEQ video talks about the need to decolonise the story of migration. What would that look like and how would it shift the perspective from the current narrative?

Teye: Decolonising the story means that the writing on migration, the research, the storytelling should be led by scholars from the Global South working with scholars in the Global North. Scholars in the Global North tend to misunderstand or misinterpret mobility patterns. For instance, because they are in Europe, they just see an influx of people coming to Europe, especially since 2015.

So, when the story is led by people that only see the people coming and they don't see the other people that are circulating within the region, they will not be able to tell our story better than we can. That is why we think the knowledge production has to shift towards the Global South, so that we decolonise that knowledge.

Decolonising the story of migration is now even more needed than before. Since 2015, there have been increasing narratives about the exodus of people from the Global South towards the Global North, with some media outlets and politicians suggesting so many restricting policies to be implemented.

The narratives have to change, and the narratives can only change when we decolonise the knowledge.

The New Humanitarian: What exactly is South-South migration, why is it overlooked by media narratives driven by the Global North, and what is important to understand about it that is absent from those narratives?

Teye: South-South migration basically means migration movement between and among developing countries. If you take West Africa, migration movement within West Africa or even between West Africa and Asia, or between West Africa and Latin America would constitute South-South migration.

It has not really been discussed in the mainstream literature for a long time because the people that have had the chance to write about migration are scholars from the Global North. So most of the things they write are based on people moving into the Global North. Also, all the large scale research funding agencies are located in the Global North. So they tend to be more interested in funding projects that look at migration towards the Global North.

Things are changing in recent years. For instance, the European Union, the UK, and other governments are beginning to fund research within the Global South. But still there’s a lot to be done when it comes to South-South migration. If you look at the volume of publications on South-North migration, it’s much higher than what is published on South-South.

People also did not think that South-South migration can contribute to a reduction in inequality and the achievement of the SDGs [UN Sustainable Development Goals]. We know that is not true because, on the ground, South-South migration has the same potency to contribute to inequality, but also to reduce inequality – just as the South-North migration.

The New Humanitarian: What is the relationship between migration and inequality, both within and between countries?

Teye: On one hand, migration can be driven by inequality between countries, and inequalities also influence who migrates. Even when people are faced with the same economic challenges, the same environmental challenges, not all of them will be able to migrate. Especially if you are talking about migrating to Europe from Africa, you need some resources.

There are also gender differences. Sometimes you have patriarchal norms, rules, traditions that will not allow women to migrate. Gender inequalities can prevent some people from migrating.

Migration can also cause inequality. Poor migrants often experience labour exploitation, and rich migrants can exploit the labour of people in the countries they move to. When people move from relatively more developed countries to poorer countries, they can also contribute to destroying the environment. For example, people have moved to West African countries to extract resources, and then they are not implementing proper environmental management strategies. That is a source of inequality.

But migration can also reduce inequality. So if the poor get the chance to migrate and then they are able to work, it means that the inequality gap is being closed. Some people can only do well if they migrate. That is why migration is good.

If you look at climate change, for instance, in areas seriously affected by environmental stress – no rainfall, they are not able to produce – such as in the Sahel region in West Africa – then one of the surest ways to reduce the inequality between those communities and other better off communities will be migration. People also migrate to enhance the livelihoods of their families left behind. So poor families have the money to send one person to another country and he finds a good job, remittances sent back can help to reduce inequality.

The New Humanitarian: What impact has the COVID 19 pandemic had on the inequalities associated with migration?

Teye: Specifically in the China-Ghana corridor, the suspension of flights between the two countries affected regular migration flows. In both countries, rich migrants were able to migrate through chartered flights while the low-skilled migrants were trapped. They were also not able to work, which means that they faced more problems.

The economic challenges that we are facing due to restrictions are also worse when we talk about those that are poor. In China, those that were working for companies were able to receive their salaries and work from home whereas those who were working as domestic workers and others could not work. In Ghana, migrants in the informal sector were hit hard because they could not work during lockdown.

In Ghana, and most West African countries, governments have now opened the borders for airlines, but then they are not opening the land borders, and the land borders are used by poorer people. So poorer people are still restricted. They are trapped. When it comes to access to healthcare, it was also the same thing. Many of the poor migrants struggle to access COVID-19 tests, vaccination, or treatment.

The stimulus packages that were implemented by governments also did not benefit the poor. In Ghana, for instance, a lot of money was pumped in to help businesses to survive during COVID. But the business needed to be registered. Many of the immigrant businesses are not registered because they are small-scale businesses in the informal sector, so they didn’t qualify to get the stimulus packages that were being given out.

The New Humanitarian: What is the relationship between South-South migration and humanitarian crises – what is important to understand about South-South migration in the context of humanitarian crises?

Teye: Humanitarian crises are leading to increased South-South migration, especially related to climate change. For example, parts of Burkina Faso, Niger, Nigeria, and Chad are all facing climate change, which is also producing insecurity in the region because you have conflicts as a result of limited resources. Food insecurity has also increased famine and caused people to move within those countries. Most of these people are not able to move internationally.

When people are moving from West Africa to Europe, most of them will pass through Agadez, Niger. But most of the people migrating from Niger do not go to Europe. They come south to Cote d’Ivoire and Ghana because these are relatively poor communities. They don’t have the resources to go to Europe. So, poor people fleeing areas facing environmental challenges are likely to move just short distances.

Climate change, security issues, forced displacement are all humanitarian crises driving South-South migration.

The New Humanitarian: You mentioned that the funding situation for research on South-South migration has improved a little bit recently. But MIDEQ has been affected by the funding cuts in the UK. What impact are those cuts having on the project?

Teye: It’s important for me to clarify: The funding issue was very bad in the past, and it has not improved tremendously. Now, there are a couple of mostly small-scale projects largely focusing on South-South migration. So I was just comparing with the past when there was almost nothing. Compared with research on South-North migration or North-North migration, research on South-South migration is still very limited.

We were looking at how to engage policymakers and communities to maximise the developmental benefits of migration, protect the human rights of migrants, and ensure our findings were used to contribute to the achievement of the SDGs. All of these things are at risk now.

If MIDEQ ends because of budget cuts, it means that there will be no major project in the world looking at South-South migration.

The New Humanitarian: To circle back to the idea of decolonising the story of migration…

Teye: That would be the end of decolonising knowledge production on migration.

This article was originally published by The New Humanitarian, a news agency specialised in reporting humanitarian crises.