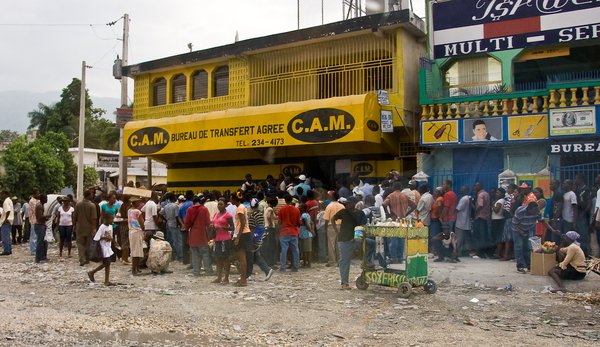

"Haiti all the way!" by caribb is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

This article was originally published on the United Nations University: Centre for Policy Research (UNU-CPR) website. More details on UNU-CPR can be found here.

As Lula is sworn in as President, Heaven Crawley reflects on what his election might mean for Haitians living in Brazil, for whom access to rights and opportunities for integration have proved elusive.

On 1 January 2023, Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva became President of Brazil, a post he previously held for two terms between 2003 and 2010. The Presidential ceremony was deeply symbolic, intended to signify a shift away from the approach taken by Jair Bolsonaro, whose four-year term in office was marked by a rolling back of indigenous rights and significant anti-immigrant rhetoric.

In an emotionally charged victory speech, Lula vowed to rebuild the country, improve the lives of poor Brazilians, work towards racial and gender equality, and achieve zero deforestation in the Amazon rainforest.

Expectations for Lula’s return are high, including among Haitian migrants who arrived in Brazil following the massive earthquake that devastated their country in 2010. Many still struggle to secure access to justice in a country built on the enslavement of indigenous peoples and millions of black Africans.

The legacy of slavery

Brazil has a long and complicated migration history – which continues to affect people of African descent. An estimated 5.5 million African slaves were brought to Brazil to work in the country’s sugar-based plantation economy – and when slavery was eventually abolished in 1888, far later than any other country in the Americas, the lives of Afro-Brazilians did not change drastically.

Many freed slaves entered into informal agreements with their former owners, exchanging free labor in return for food and shelter.

White Brazilian elites, concerned they could become a minority, also implemented a policy of branqueamento, or ‘whitening,’ through European immigration which aimed to limpar o sangue (cleanse the blood). This was justified on the grounds that Brazil could not flourish with a largely black population, a legacy that continues today through deeply racialized institutional structures and attitudes prevalent throughout contemporary Brazilian society; reflected in widespread human rights abuses towards Afro-Brazilians and poverty rates that are twice those of white Brazilians.

Haitian migration to Brazil

Haiti has its own history of slavery. After securing independence and abolishing slavery, Haiti was severely punished by the international community and forced to make huge debt repayments to France, pushing the country into a cycle of debt that hobbled its development for more than 100 years. Once the wealthiest colony in the Americas, Haiti is now the Western Hemisphere’s poorest country, with more than half of its population living below the World Bank’s poverty line.

The massive earthquake that shook Haiti in January 2010 swept away the country’s capacity to deal with the systemic problems it faced. It also led to the large-scale displacement of Haitians looking for ways to feed themselves and their families. Although Haitians had not previously migrated in large numbers to Brazil, word spread about opportunities there, particularly in the lead-up to the 2014 World Cup and the 2016 Olympics Games.

In 2012, as a response to the increase in the number of Haitians claiming asylum in Brazil, the government opened up an opportunity for Haitians to regularize their status through humanitarian visas. As of 2020, the Haitian population living in Brazil was estimated to be around 143,000.

The experience of Haitian migrants

Humanitarian visas provide opportunities for regular migration for those who do not qualify for protection under the Refugee Convention but are unable to remain in their own countries. Yet more than a decade after their introduction, the lives of Haitians in Brazil are characterized by a profound ambivalence: on the one hand a system has been created to draw them to the country, but on the other their reception is arbitrary and unplanned.

Our work with the MIDEQ Hub and its local partner, the Instituto Maria e Joao Aleixo (IMJA), has highlighted three main issues.

Firstly, although the right to family life is enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, many Haitians are unable to arrange for their families to join them in Brazil. Family reunion is difficult in Brazil, even for those who have refugee status, and humanitarian visas do not come with the same protections and government resources. Many Haitians have difficulties securing the necessary documentation to be reunited with family members.

Furthermore, they face challenges associated with travel to and from Haiti due to a lack of direct flights since the COVID-19 pandemic and transit visa requirements. This problem has been exacerbated by the rapid deterioration in security in Haiti following the assassination of President Moïse in July 2021. Unable to protect their families in Haiti, or even contribute to meeting their immediate needs, Haitians in Brazil feel helpless and hopeless. They also feel frustrated by the Haitian government’s inability to support them, including through the provision of documentation.

Secondly, the economic opportunities that many Haitians believed would be available to them in Brazil have proved to be elusive. There is evidence that Haitian quake survivors were forced to endure work conditions akin to modern slavery while building a multi-million dollar stadium for the 2014 World Cup and during construction work for the Olympics. Moreover, qualified migrants are often unable to get their skills and qualifications recognized due to the cost and complexity of the Brazilian authentication process. When Brazil fell into an economic recession in 2014, many Haitians were left without employment and fewer pathways to permanent legal status.

Finally, responses to the migration of Haitians have been deeply racialized. Without relatives and friends, most non-white migrants in Brazil live in the suburbs, peripheries, and favelas. They find it extremely difficult to secure regular jobs due to xenophobia, racism, and social class prejudice. Haitians and other black migrants have also been the victims of physical violence.

What next for Brazil’s Haitian community?

Lula inherits a deeply unequal country, one which was hit hard by the COVID-19 pandemic and is politically polarized: he won the election by less than 2% of the vote and as the attacks in Brasília demonstrate, opposition supporters continue to dispute Lula’s victory.

Despite lifting millions of people out of poverty over recent decades, Brazil still faces a huge gap between the country’s richest and the rest of the population, including black migrants and indigenous Afro-Brazilians.

But Brazil’s potential is also huge and Lula’s return marks a potentially important turning point. The country has already started to reverse its isolation on the international stage, announcing its return to the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration which signals Lula’s intention to address the issues facing migrants in Brazil.

He can also reframe migration narratives – shifting the anti-immigrant narratives that dominated Bolsonaro’s presidency and undermined the rights of Haitian migrants and promoting the potential for migration to become a driver of development.

Lula needs to further address the specific issues facing the Haitian community who, more than a decade since the earthquake, remain unable to secure access to rights and opportunities for integration in Brazil. Immediately after the earthquake, then-President Lula visited Haiti and said that Haitians could come to Brazil and that they would be received with open arms. Now is the time to translate that welcome into action, addressing the pressing issue of family reunion in the context of Haiti’s increasing insecurity and economic precarity.

Finally, Lula, who identifies as black, has committed himself to addressing the structural racial inequalities that shape the lives of indigenous, black, and Afro-Brazilian communities. His decision to appoint the sister of murdered anti-racist activist Marielle Franco as Brazil’s new Minister of Racial Equality is a signal that he intends to rebuild the anti-racist laws and policies dismantled over recent years. Given Brazil’s history, this may well prove to be the most important change.