Students of Christ the King School, Accra who participated in one of the discussions of the Ghana Must Go event. Photographer: Marisa Claire Andoh.

MIDEQ’s political mobilisation and transnational solidarity thematic area focused on political mobilisation and worker rights over the course of the project. Through our case studies in our own countries of research interest (Ghana, Burkina Faso, South Africa, Ethiopia), as well as listening to colleagues across the Hub, it has become abundantly clear that worker rights are routinely abused across the globe on a regular basis. There are many efforts to address these indignities. These include micro level efforts such as identity-based associations that migrants form to tackle the many oppressions they face, meso-level activities such as unionisation, and macro level efforts such as protests. Citizens sometimes offer support by organising protests where migrant associations can make their unique needs heard.

We find these forms of solidarity particularly powerful because they recognise the common humanity of us all. Whether citizen or migrant, each individual has basic human rights that must be adhered to at all times. Secondly, citizenship status does not make one immune from experiencing the second-class citizenship status that immigrants experience. Even individuals currently located in their countries of origin, may one day migrate or have relatives who are potential migrants. Their rights as citizens may also be violated. Thus, the needs of migrants must be of concern to both citizens and migrants. This is a message that we wanted to entrench in the younger generation in Ghana. The 40th anniversary of the mass expulsions of Ghanaians from Nigeria, known as the ‘Ghana Must Go’ episode provided a perfect opportunity for doing so.

Students of Christ the King School, Accra who participated in one of the discussions of the Ghana Must Go event. Photographer: Marisa Claire Andoh

A brief history of ‘Ghana Must Go’

In the late 1970s as the economic situation in Ghana deteriorated, many Ghanaians went to Nigeria in search of greener pastures. The exact number is difficult to estimate: figures provided by official sources in both Ghana and Nigeria put the number at between one to two million respectively while academics such as Samuel Daly suggest that it was probably in the hundreds of thousands. Considering that Ghana’s population in 1984 was 12.3 million, even the modest figure offered by academics suggests that a sizeable proportion of Ghana’s population resided in Nigeria at the time: 600,000 people would have constituted 5% of Ghana’s population. Some of these people were professionals such as nurses, teachers and university lecturers while others were artisans such as barbers, masons, carpenters and traders. These individuals worked, took care of their families and saved as much money as they could. All was well until 1983.

The deportation order

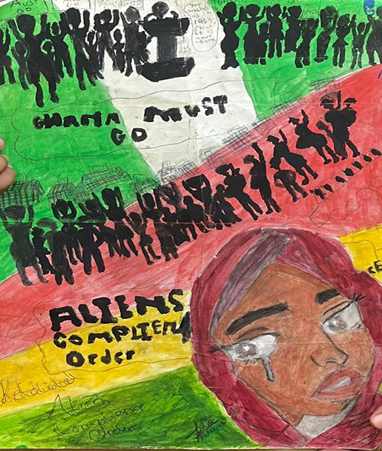

On 17th January, 1983, facing economic crisis and a sense that migrants were taking on jobs meant for locals, the then Minister of Internal Affairs in Nigeria, Alhaji Ali Baba, made a public announcement that all unskilled migrants in Nigeria as well as those without residence permits were to leave the country within a fortnight. The deadline was extended for another four weeks, but six weeks was little time to organise a proper return home. As a result, many Ghanaians packed their belongings into what has now come to be known as the ‘Ghana Must Go’ bag and headed for home mostly on foot or bus. The return journey was perilous with some losing their lives in the process. Those who made it safely back home look back on that episode in their lives with much regret as evident in the voices of the 36 returnees we interviewed as part of this project. For example, in the words of one man who migrated to Nigeria as a thirteen-year-old, “Personally, I will say a journey to Nigeria is not worth taking…It affected my academic progression…You can visit any country of your choice but I wouldn’t advise you to visit Nigeria.”

The importance of memory

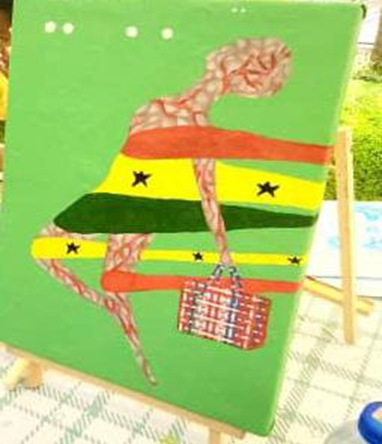

The individuals with lived experience of that period in Ghana’s history are now in their late 50s at least. Many others have passed on with their stories shared only with family members. For the younger generation born in the 1990s and beyond, this episode in Ghana’s history is far removed from their reality: it happened before they were born and there is little public discussion either in schools or on mass media. Ghanaian experiences of migrant status and what it teaches us about the importance of solidarity is therefore limited. We wanted to revisit this episode in Ghana’s history as an opportunity to teach lessons about migrant solidarity. To do it in a manner that would have a lasting impression on the children, we chose to launch a painting competition. Students in the art classes at Christ the King School, Faith Montessori School and Martin De Porres School were invited to participate in the competition.

The lessons of the ‘Ghana Must Go’ event

To provide context for the competition, MIDEQ researcher Akosua K. Darkwah visited the Christ the King School as well as Martin de Porres School and narrated the history of this period. Great effort was placed not only on giving the children a vivid sense of how the migrants felt but also how much support they got from ordinary Nigerians both before and after the eviction order. There was also a conversation about the arbitrary manner in which our borders divide us, particularly given that Ewe speakers can be found on both the Ghanaian and Togolese sides of the border, just as Akan speakers can be found in Cote d'Ivoire and Ghana.

Our common humanity regardless of national origin or citizenship status was emphasised. The children asked great questions about what this episode teaches us about Pan African solidarity, what it must have felt like to be expelled and to have to leave loved ones behind and so on. The children then went off to convert their understandings into meaningful paintings. Below are the pieces that won first and second prize chosen by a team of Ghanaian female artists. Most importantly, we trust that the larger lesson of adhering to the Golden Rule, treating each other as one would like to be treated, has been reinforced for winners and non-winners alike.